Uber’s Rate Limiting System

Uber’s service-oriented architecture processes hundreds of millions of RPCs (remote procedure calls) per second across thousands of services. Keeping this system reliable requires strong overload protection, ensuring that no single caller, client, or service can overwhelm another.

To achieve this, we set out to design a rate-limiting service that would make it easy for services to configure limits per caller or per procedure, without code changes. This service, later known as the GRL (Global Rate Limiter), integrates directly into the service mesh, which relays RPC requests for most of Uber’s services.

Over time, that foundation evolved into a fully automated control system powered by the RLC (Rate Limit Configurator), which keeps limits fresh and accurate based on historical world traffic patterns.

Together, these systems ensure that Uber’s platform remains resilient, even as it processes hundreds of millions of requests per second across thousands of microservices.

In distributed systems, rate limiting is a foundational mechanism for maintaining reliability and fairness. It protects shared services from overload, prevents cascading failures, and ensures that no single caller can consume disproportionate capacity.

The most common distributed design uses a distributed counter store, often implemented with Redis®. Each request increments a key representing a caller or endpoint, and the system rejects requests once the counter exceeds a configured threshold. For many applications, this approach provides a simple, effective balance between accuracy and cost.

In the early days of Uber’s microservice architecture, there was no single way to protect services from traffic overload. Teams implemented their own throttling logic, sometimes within business logic, sometimes through custom middleware or Redis-based counters. Each approach worked for its owner, but created systemic inefficiencies:

- Inconsistent configurations. Different implementations enforced limits differently, leading to different behaviors even with identical quotas.

- Operational overhead. Redis-based limiters added latency and required fleet management.

- Operational friction. Updating rate limits often required redeploying servers, delaying responses to changing traffic patterns.

- Maintenance risk. Fragmented, less-documented limiters created operational risk by being difficult to locate or modify during incidents. Furthermore, reliance on external dependencies like Redis introduced hidden complexity and the potential for unexpected behavior changes, such as those caused by library upgrades.

- Uneven protection. Many smaller services ran without any limiters at all.

- Limited observability. Because each limiter reported metrics and errors differently, there was no unified way to determine whether a failure was caused by rate limiting or another issue.

Using a distributed key–value store like Redis as a centralized counter for rate-limiting might have seemed viable. However, this model couldn’t scale to Uber’s fleet, with hundreds of thousands of hosts handling hundreds of millions of requests per second across multiple regions. Each request would need to increment and read counters remotely, introducing unacceptable latency and cross-region consistency challenges. Even with sharding and replication, hundreds of Redis clusters would be required to maintain accurate global state in real time, adding operational complexity and new failure modes.

We also ruled out periodic synchronization of counters because it’d reduce network overhead but produce stale data and slow reactions to sudden traffic spikes.

The team ultimately concluded that a fully distributed architecture, where local proxies make enforcement decisions using aggregated load instead of a central counter, was the only way to achieve both low latency and global scalability.

The solution was to integrate rate limiting into Uber’s service mesh, the infrastructure layer for inter-service RPC traffic.

Embedding the limiter at this layer allowed every request to be inspected and evaluated before reaching its destination, independent of the caller’s language or framework.

The goal was ambitious: Provide a unified rate-limiting service that makes it easy for any team to configure per-caller or per-procedure quotas, without code changes.

The design also needed to scale to hundreds of millions of requests per second, tens of thousands of service pairs, and across a fleet of hosts in different geographical regions, with minimal added latency.

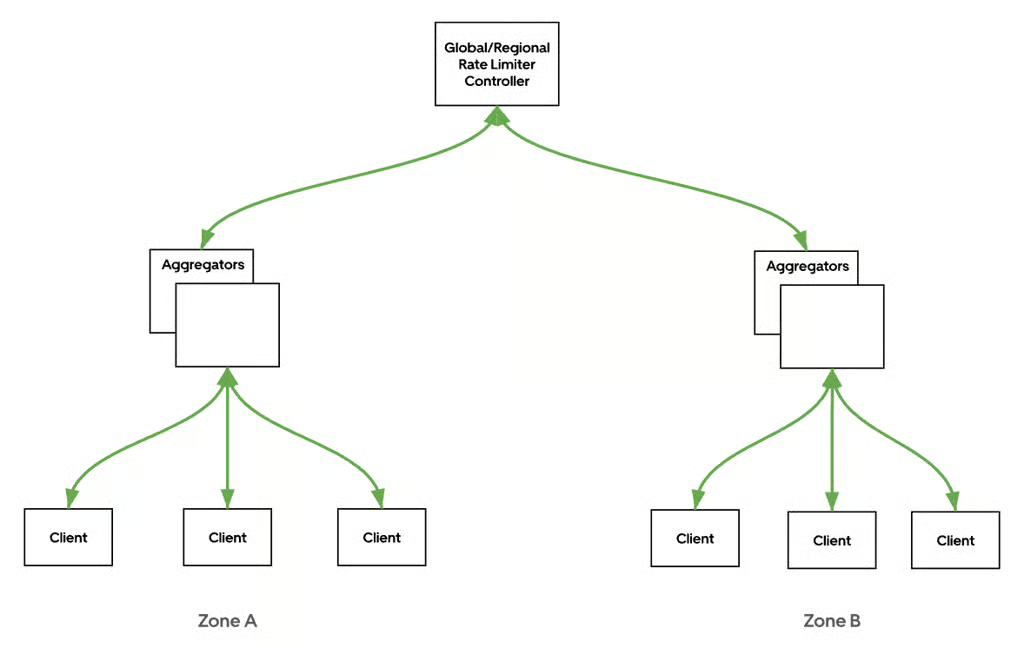

At its core, GRL introduced a three-tier feedback loop.

-

Rate-limit clients (in the service mesh data plane). Enforce per-request decisions locally based on directives received from aggregators. Report per-host request counts per second to zone-level aggregators.

-

Aggregators (per zone). Collect metrics from all clients in the same zone and compute zone-level usage and send it upward to controllers.

-

Controllers (per region, global). Aggregate zone data to determine global utilization and push updated drop ratio directives back down to aggregators and clients.

This hierarchical aggregation ensured low latency in the hot path (decisions are local) while maintaining global coordination within a few seconds. If the control plane became unavailable, clients failed open, allowing traffic to continue rather than risk self-inflicted outages.

Figure 1: The three-tier architecture of the GRL (Global Rate Limiter) showing clients, zone-level aggregators, and regional/global controllers.

When the GRL (Global Rate Limiter) project began, the team initially implemented a token-bucket algorithm for enforcement on each proxy in the network data plane. Each proxy locally tracked request counts and replenished tokens over time, allowing or rejecting requests based on the number of available tokens.

The token rate was derived by comparing the proxy’s local load to the global limit. The proxy calculated a ratio between its observed traffic and the global load target, and then replenished tokens accordingly (at ratio × limitRPS).

If a request arrived while tokens were available, it was allowed and one token was consumed. If not, the request was marked as rate-limited. To handle bursty or uneven traffic, the client stored unused tokens in a circular buffer, allowing them to be spent during brief surges.

By default, tokens could be retained for up to 10 seconds, configurable up to 20 seconds for services with higher burstiness.

While this approach worked in early testing, it revealed scalability and fairness issues in production. One issue was unfair caller distribution. When the number of callers exceeded the configured limit, the token bucket couldn’t fairly divide capacity among them. Another issue was instance-level spikes. Individual hosts with bursty traffic could start dropping requests prematurely, even when overall load was still below the global limit.

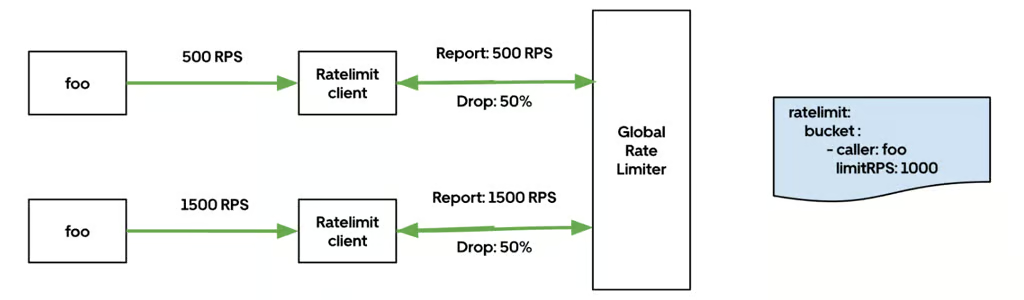

To mitigate these limitations, the team introduced drop-by-ratio, a feature that adjusted behavior when aggregated global load exceeded the configured limit. When this happened, clients began probabilistically dropping a percentage of requests across all instances of an overloaded caller.

For example, if a caller’s aggregate RPS was 1.5 times its limit, all its instances would start dropping roughly 33% of requests, calculated as:

drop_ratio = (actual_rps - limit_rps) / actual_rps

This global drop signal, updated by the control plane every few seconds, ensured that excess traffic was evenly throttled across all caller instances rather than relying solely on per-host token states.

Drop-by-ratio proved particularly effective for large gateway-style services with hundreds or thousands of caller instances, where per-host token accounting couldn’t capture global load distribution.

As GRL matured, the team fully deprecated the token-bucket mechanism in favor of a control plane driven probabilistic dropping model, where all enforcement decisions are based on aggregated load rather than local counters.

Maintaining both algorithms simultaneously had increased configuration complexity and network overhead as each client needed to exchange periodic load reports with the control plane to keep token rates aligned.

By consolidating around a single model, GRL simplified configuration, reduced control-plane bandwidth, and unified all rate-limit decisions under a globally consistent mechanism. The trade-off was that rate-limit decisions now depend on globally aggregated data updated every second, meaning enforcement can lag by up to 2 to 3 seconds behind real-time traffic conditions.

In practice, this delay has proven negligible for nearly all workloads and it rarely affects rate-limit accuracy except when a caller generates a very short, extremely high burst of traffic. This slight delay was acceptable compared to dropping valid traffic prematurely while the system as a whole remained under capacity.

In the current GRL model, enforcement happens entirely at the client layer within the network data plane. Each proxy receives rate-limit configurations and drop-ratio directives from the control plane.

- The client matches the request against configured buckets, defined by caller, procedure, or both.

- If the request matches a bucket that has a current drop ratio directive, the client probabilistically drops a percentage of requests according to that ratio.

- If no drop directive is active for that bucket, the request is forwarded normally.

This approach keeps the hot path extremely lightweight—there’s no local token accounting or per-request communication with the control plane. All decisions are made in-process, using simple probabilistic sampling.

The aggregators and controllers perform the more complex calculations external to the forwarding plane: they aggregate request counts, compare them to configured thresholds, and compute new drop ratios every second.

These updated ratios are pushed down to all connected clients, enabling global coordination with minimal latency and no centralized bottleneck.

This design allowed GRL to scale to hundreds of millions of requests per second while maintaining consistent global enforcement accuracy within a few seconds of lag.

Figure 2: Final GRL design with control-plane-directed probabilistic dropping model.

Service owners defined rate-limit buckets in configuration files. Each bucket could specify:

-

Scope: global, regional, or zonal.

-

Matching rule: caller names, procedures, or both.

-

Behavior: deny (enforce) or allow (shadow mode for testing).

GRL applies these limits transparently with no code changes required for the destination service.

The introduction of the GRL produced measurable improvements in both reliability and performance across Uber’s service mesh.

Before GRL, many services relied on Redis-backed limiters that required a network round-trip for each request. By moving rate limiting directly into the service mesh data plane, rate limits could be evaluated locally, thus eliminating that additional hop and reducing latency substantially.

Latency improvements were observable across multiple services. The distribution in Figure 3 shows how requests shifted toward lower-latency buckets immediately after removing its Redis-backed limiter and migrating to GRL for one of Uber’s large critical services.

| Request Latency | Before (RPS) | After (RPS) | Change |

| 2–3 ms | 2.5K | 30 K | +1100 % |

| 3–4 ms | 50K | 170 K | +240 % |

| 4–5 ms | 120K | 120 K | 0 % |

| 5–6 ms | 80K | 34 K | −57.5 % |

| > 6 ms | 100K | 20 K | −80 % |

Figure 3: Request distribution shift to lower latency after migrating a critical service to GRL.

Across key API endpoints, latency improvements were consistent at every percentile. Median (P50) latencies decreased by around 1 millisecond, while 90th percentile (P90) latencies dropped by dozens of milliseconds. At the tail (P99.5), requests that previously took several hundred milliseconds were reduced to tens of milliseconds, representing up to a 90% improvement in the slowest response times.

Figure 4: Latency improvements across key API endpoints after migrating to GRL.

These gains highlight how removing the external Redis dependency and handling rate limiting locally within the data plane significantly improved both median and tail latency performance.

Centralizing rate limiting inside the service mesh data plane also simplified the infrastructure. Services no longer need to maintain separate data stores or caching layers for quota enforcement, reducing operational overhead and improving consistency. The migration delivered a meaningful compute efficiency gain, freeing up a substantial number of Redis instances that had previously been dedicated to rate limiting workloads.

Since deployment, GRL has repeatedly prevented overloads during spikes, failovers, and retry storms.

By probabilistically shedding excess traffic in the service mesh, services now maintain consistent response times even during abrupt surges in incoming load.

Figure 5: A critical service survived a 15× traffic surge (22 K → 367 K RPS) without degradation.

Figure 6: A DDoS attack was absorbed before reaching internal systems.

Beyond automatic protection, GRL is also a trusted part of Uber’s operational playbook. During active incident mitigation, Production Engineering teams routinely use GRL to apply targeted rate limits on high-traffic callers or procedures. With control-plane updates propagating every second, GRL can react to overload conditions within seconds, allowing teams to contain traffic surges quickly and safely without redeployment.

This ability to throttle specific traffic patterns quickly and safely without requiring service redeployments has made GRL one of the most dependable tools for containing overload conditions in production.

At full scale, GRL now processes around 80 million requests per second across more than 1,100 services, enforcing quotas dynamically while keeping end-to-end latency low. This combination of latency reduction, resource efficiency, and predictable global enforcement established GRL as a cornerstone of Uber’s reliability platform and laid the groundwork for the next phase: automating rate-limit configuration at scale.

While the GRL (Global Rate Limiter) unified enforcement, configuring limits still required manual effort. Service owners defined YAML files describing per-caller and per-procedure quotas and had to adjust them whenever traffic patterns changed.

At Uber’s scale, where hundreds of microservices evolve continuously, these static configurations quickly became stale.

- Too strict: services throttled even during healthy traffic peaks.

- Too lenient: limits were set far above real capacity, offering little protection.

- Too manual: changes depended on humans analyzing dashboards and tuning numbers by hand.

To keep up with constant change, rate-limit management itself needed automation.

The RLC (Rate Limit Configurator) was built to keep GRL configurations accurate and up-to-date automatically. It periodically analyzes live traffic metrics and rewrites rate-limit settings based on observed demand.

On a fixed schedule or immediately when a configuration changes, RLC performs the following cycle:

- Collect metrics from Uber’s observability platform for the past weeks.

- Compute safe limits for each caller or procedure using historical peaks and buffer headroom.

- Write updated configurations to the shared configuration repository.

- Push new limits to the Global Rate Limiter through the existing control plane.

This closed-loop process ensures that limits evolve with real traffic, minimizing human intervention while maintaining overload protection.

RLC was designed from the start to support multiple rate-limit calculation strategies. While the default policies rely on historical RPS data, the system’s architecture allows new policy types to be added seamlessly as Uber’s traffic models and service needs evolve.

For example, some services such as those powering mapping and location data, use predictive models that incorporate traffic forecasts and pre-planned capacity to calculate rate limits. These models anticipate future load rather than reacting only to historical trends.

In other cases, a fixed quota is allocated to each caller or service. These quotas change less frequently and are governed by pre-determined contractual or operational agreements, offering predictable, long-term limits.

By supporting multiple policies through a modular interface, RLC can tailor rate-limit calculations to different service domains whether the service relies on near-real-time traffic patterns, forecasts, or static quotas.

To ensure safety, teams can configure rate limits on shadow mode, where limits are generated and monitored but not enforced. This allows service owners to observe how rate limiting would behave in production before activating it. Dedicated dashboards and alerts visualize both observed traffic and hypothetical drops, providing confidence before rollout.

Automating rate-limit configuration delivered immediate benefits:

- Operational simplicity. Thousands of rate-limit rules now update automatically without manual edits.

- Consistency. Policies are generated from the same formulas and data sources across all services.

- Flexibility. Different policy types allow teams to select or extend calculation logic best suited for their workloads.

- Safety. Shadow mode ensures correctness before enforcement.

The Rate Limit Configurator transformed GRL from a static safety layer into an adaptive, extensible, self-maintaining system.

While the Rate Limit Configurator keeps Uber’s rate limits accurate and up to date, the journey continues. In recent years, the team has expanded buffer tuning, introduced regional rate limits to reduce the blast radius of configuration changes, and increased update frequency to make the system even more responsive to live traffic. These efforts are complemented by Uber’s throttler layer, which provides additional overload protection closer to the application.

Today, the Global Rate Limiter is a key component of Uber’s multilayered reliability stack, ensuring that even under extreme load, Uber’s platform remains stable and fair.

Uber’s rate-limiting system shows how deep infrastructure investments evolve, from fragmentation and manual operations to unified automation at scale. The Global Rate Limiter provided the foundation for consistent protection, while the Rate Limit Configurator made that protection self-adjusting and effortless to maintain.

Today, Uber’s rate-limiting systems operate autonomously at massive scale, keeping traffic safe, latency low, and engineering teams focused on building features rather than managing configuration.

Redis is a registered trademark of Redis Ltd. Any rights therein are reserved to Redis Ltd. Any use by Uber is for referential purposes only and does not indicate any sponsorship, endorsement or affiliation between Redis and Uber.