Task-Oriented Conversational AI in Airbnb Customer Support

How Airbnb is powering automated support to enhance the host and guest experience

Customer Support (CS) can make or break a guest’s travel experience. To support Airbnb’s community of guests and Hosts, we have been investing heavily in developing intelligent CS solutions leveraging state-of-the-art natural language processing (NLP), machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

In this blog post, we’ll introduce the automated support system at Airbnb, which employs the latest task-oriented conversational AI technology, through the lens of a recently launched feature called Mutual Cancellation. We will describe in detail how we framed the business problem as an AI problem, how we collected and labeled training data, how we designed and built the ML models, and how the models were deployed in the online system. Throughout each step, we’ll discuss some technical challenges we faced during this project and the solutions we innovated to address these challenges.

A Case Study: Mutual Cancellation

Prior to the development of the mutual cancellation model, guests needed to involve CS agents, even if they had already reached an agreement with the host for canceling a reservation. This meant that issues took longer to get resolved and precious CS agent hours were wasted. To solve this issue, we developed AI models that help guests and Hosts self-resolve cancellation and refund issues without involving a CS agent. This empowers hosts and guests to decide what is best for them, while allowing us to focus CS agent hours where they are needed most.

In the rest of the post, we will use the mutual cancellation feature as an example to describe the technical components of Airbnb’s task-oriented AI system.

System Architecture

Airbnb’s Intelligent Support Platform team develops cutting-edge AI technologies to help guests and hosts solve their issues in the most efficient manner. Based on the chatbot platform we built, ATIS, our AI models aim to learn and mimic how human agents provide warm and effective customer care. A warm and effective customer care experience starts with a personal and intelligent issue identification that aims to quickly understand the user’s situation, needs, questions and concerns with minimum friction.. Once the issue is clearly identified, we generate responses dynamically and guide users through various product workflows to solve their issues or route them to human agents.

Our intelligent customer support product is designed as a “task-oriented dialog system” (Zang et al. 2020, Madotto et al. 2020). Task-oriented dialog systems are gaining more and more interest in recent years, powering AI products ranging from virtual assistants to smart speakers. These models can understand the user’s intent (e.g., ‘play music’), extract needed parameters (e.g., ‘artist name and name of the song’) from the conversation, ask questions to clarify details (e.g., ‘there are two versions of this song, which one do you like to play?’), and complete the task — all while having a dialogue with the user that seems completely natural.

Figure 1. Airbnb’s Chatbot as a task-oriented dialog system. It detects user intent and generates appropriate responses and completes the task through actions.

Customer Support as a Task-Oriented Dialog Problem

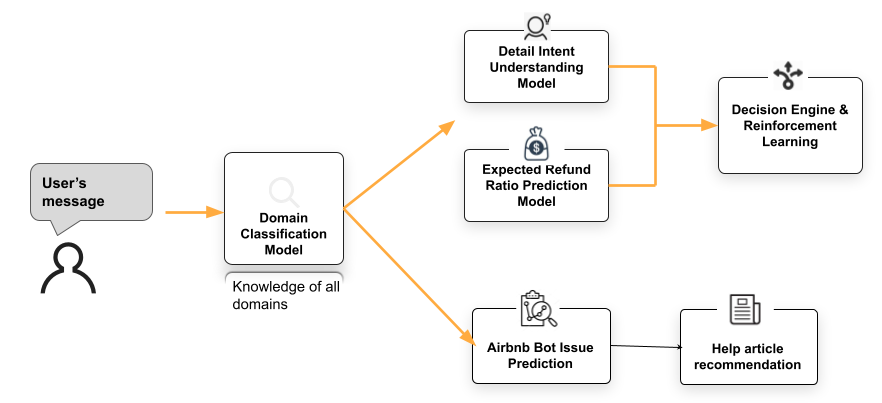

In real-world machine learning applications, the most crucial piece of the puzzle is how to formulate the problem. Problem formulation has a much more significant impact on the product’s long-term performance than the model itself. There are lots of decisions and trade-offs to be made before a single line of code is written. We designed a multi-layer issue detection and decision-making system to allow both extensibility and domain-specificity for the customer support problem, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A multi-layer user issue detection and decision-making model structure.

When a user sends a message in the Airbnb chatbot, the message is processed by the first layer, a domain classification model. The domain classification model determines which domain the message belongs to, for example, a trip rebooking request, a cancellation refund request, or a question that can be answered with a help article recommendation. If the Mutual Cancellation domain is predicted to be the most likely domain, the system triggers the Mutual Cancellation flow and enters the second layer to further our understanding of the user’s intent and checks the eligibility of the Mutual Cancellation.

For Mutual Cancellation, there are two models in the second layer: the Q&A-based intent understanding model and the “expected refund ratio prediction” model. The Q&A intent model is trained on a manually labeled dataset. The “expected refund ratio prediction” model is trained on historical cancellation data and refund ratio decided by agents. Refund ratios capture many vital characteristics of the trip that are crucial for the AI system to make decisions on behalf of human agents.

The multi-layer structure has the benefit of:

- Scalable: it allows the system to be extended to new domains and domain-specific models for existing domains won’t be affected by new domains.

- Effective: the top-level model is trained on manually labeled data which is usually high quality, but often difficult and expensive to collect. Domain-specific models are mostly trained from historical data, easy to collect but noisy and biased towards past user behavior. The multi-layer structure allows us to leverage human-labeled data to train the top-layer domain prediction model and historical data to train domain-specific models.

Collecting and Labeling Training Data

A typical task-oriented dialog system builds an intent taxonomy tree where each node represents some intent, and the nodes are mutually exclusive. Airbnb’s customer support, similar to other shared-economy customer support, users’ issues contain complex issues that are less structural than a typical online marketplace. It is challenging, if possible at all, to define a clean taxonomy tree to capture ALL users’ issues and partition them in a hierarchical tree.

In addition, a taxonomy tree usually implies that we need to traverse from the root node following a path to the leaf node. Along the path, the system asks questions (e.g., “Do you want to cancel the reservation?”) or collects more information (e.g., “Is the user a Guest or a Host?”) to decide on which branch to continue. In Airbnb’s case, users’ issues are much more complicated and may require different sequences of questions to identify the issue efficiently. For Mutual Cancellation, the first question (“if the host and guest agree with each other”) and the second question(“who initiated the cancellation”) capture different aspects of the cancellation and refund process. It can be challenging to design a simple and clean tree structure taxonomy to cover all user issues and rely on the path down the tree to collect the needed information efficiently. Instead, we model intent understanding as a Question & Answer (Q&A) problem.

A Q&A Model for Understanding User Intent

Given a user’s initial message to our CS platform, we ask a couple of questions about the user’s intent, and then have human agents/labelers answer those questions. Through this setup, we collect data and train a Q&A model. The trained Q&A model is able to answer those questions similarly. Users’ questions can have multiple answers and users often try to describe the problem from different angles. In some cases, the questions can be mutually exclusive, whereas in other cases the questions may contain redundant information.

Below are a few examples we ask our labeler team:

User’s message to Airbnb:

Hello! I made a reservation wrongly. Thinking it was a whole apartment rental when it was actually just a room. I didn’t pay attention. I immediately spoke to my host, she agreed to refund me and asked me to request the refund money from the app, but I can’t find the option.

Question: Who initiated the cancellation?

Answer:

- The host initiated the cancellation, or the host could not accommodate the guest

- The guest initiated the cancellation

- Not mentioned

Question: Do the host and guest agree on a refund?

Answer:

- Host agrees on offering a refund and the refund amount

- Host and guest are having some differences on the refund amount

- Host disagrees with issuing a refund or already declined it

- Agreement not mentioned about refund

- Refund not mentioned at all

Question: Is the guest asking how they can get what they want? (how to get refund, what to do, etc)

Answer:

Question: Is the guest asking how they can get a refund, if is it possible, or how much refund can they get?

Answer:

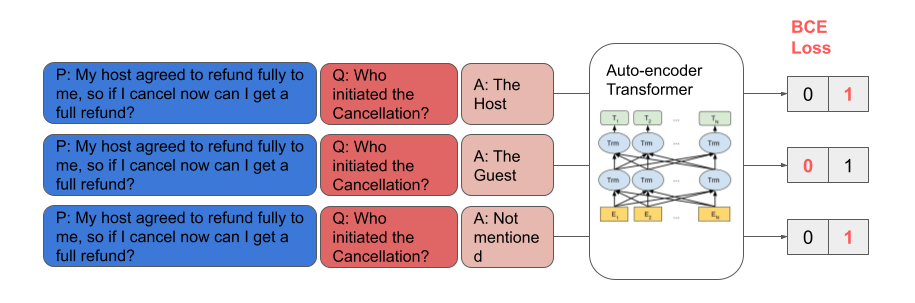

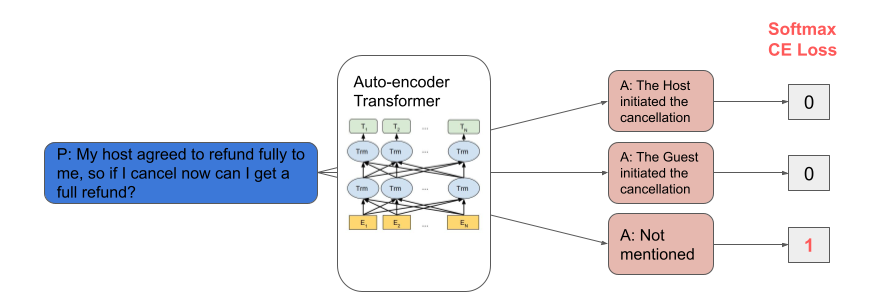

Q&A problems with multiple-choice answers are normally modeled as a multi-class classification problem, where each class maps to one question. However, Jiang et al. (2020) proposed the idea of modeling Q&A problems as single-choice binary classification problems. In modeling the problem this way, the difficulty of the problem increases. Picking the correct answer from multiple options is no longer sufficient - the model must predict the correct choice as positive and all other choices as negative. This approach makes consolidating multiple Q&A problems easier, enabling us to increase the pre-training scale. Khashabi et al. (2020) similarly found that unifying multiple pre-training datasets can help boost the model performance.

We follow the single-choice binary setup, which enables us to unify related user intent training labels from different domains to increase the scale of our training data and enhance the performance. As stated above, we continuously review the data labeling quality and refine the labeling questionnaire design. As a result, there are many versions of labeling questions and the answers for each version. A single-choice setup allows us to mix all the different versions of our training questions together in training.

Figures 3 and 4 show the difference between single-choice and multi-choice setups for an example message “My host agreed to fully refund me, so if I cancel now can I get a full refund?”

Figure 3. Single-choice Q&A model setup

Figure 4. Multi-choice Q&A setup

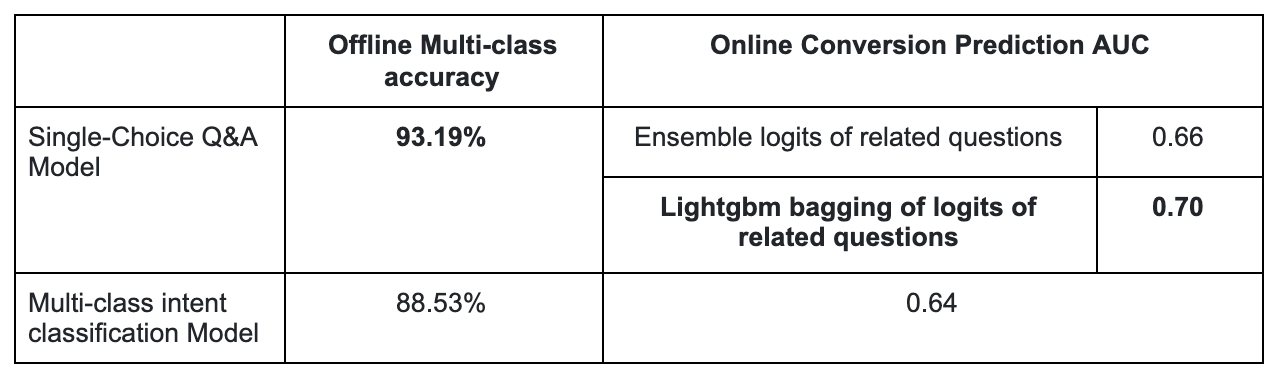

Figure 5 shows the model performance difference in our experiment. Single-choice Q&A setup outperforms traditional multi-class intent classification setup both on offline labeling prediction accuracy and on online conversion prediction.

Figure 5. Accuracy of single-choice vs. multi-class intent classification.

Benefits and Challenges of Intent Prediction as Q&A

Compared with traditional multi-class classification, the Q&A setup makes the data labeling much more manageable. We can continuously refine the questionnaire design and flexibly merge questions from different dimensions, different angles, or those with redundancy.

One of the biggest challenges of applying machine learning in real-world problems is the lack of high-quality training data. From a few-shot learning point of view, the single-choice Q&A setup allows us to build many capabilities into the model, even with sparse training data. This setup trains the model to encode information in the user message, the question and the answer. The model can also learn from related questions from other domains. For this reason, it has the capability to understand both questions in training labels and some newly constructed, unseen questions.

A shortcoming of this setup is that it puts a lot of pressure on the serving latency. For example, if we want to use the model to answer five questions and then take actions based on the five questions, we have to run the model five times. Later in this post, we’ll discuss how we reduce the model latency including using GPU.

Model Design and Implementation

We use autoencoder transformers as model architecture. We tested all kinds of model choices as the backbone. The results are shown below:

Figure 6. Results on out-of-sample data from various intent classification models.

For most of our use cases, Roberta performs the best. However, the Roberta-base and Roberta-large’s performances vary depending on the scale of training labels. In our online product case, where we have around 20K labels, the Roberta-large model achieved the best performance and is the model that we deployed in production. However, with 335M parameters, it is very challenging to run this model online with a given latency budget.

To improve the performance of this model, we leveraged three key techniques:

- Pre-training our transformer model with transfer learning;

- Translating training labels to utilize a multilingual model; and

- Incorporating multi-turn intent predictions.

Pre-training

Perhaps the most critical recent development in deep learning is transfer learning and pre-training. It dominates most state-of-the-art models in almost all kinds of NLP, computer vision(CV), and automatic speech recognition(ASR) domains.

We experimented with different pre-training methods extensively and found two pre-training methods to be particularly effective in boosting the model performance:

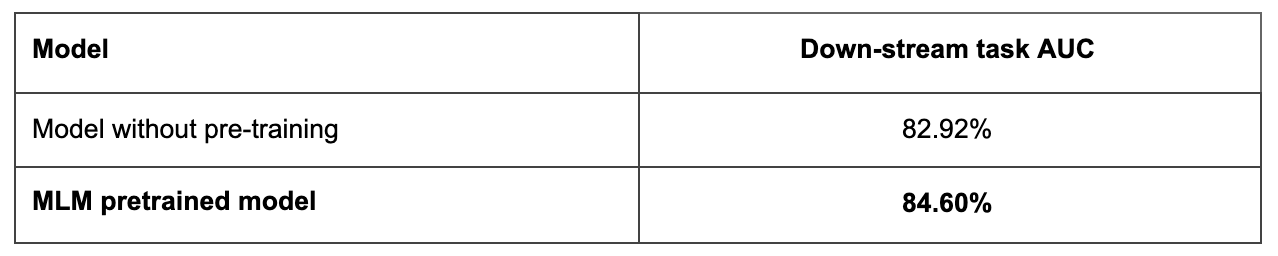

- In-Domain Unsupervised Masked Language Model (MLM) Pre-training: Based on users’ conversations with our customer service platform, the listing descriptions, and the help articles, we construct a 1.08GB (152M word tokens) unsupervised training corpus. This corpus contains 14 different languages, with 56% in English. As shown through the experiment results in Figure 7, the in-domain MLM pre-training helps to boost the model performance for our tasks.

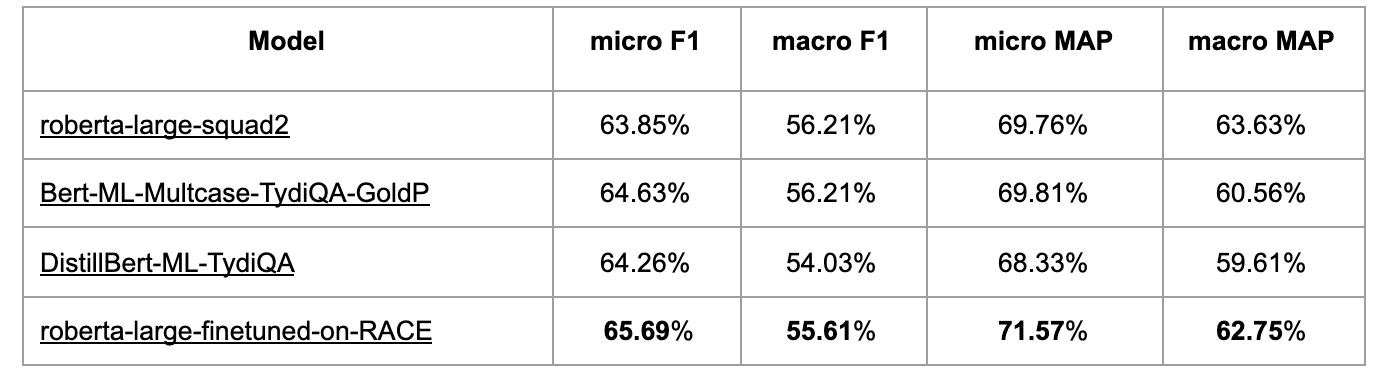

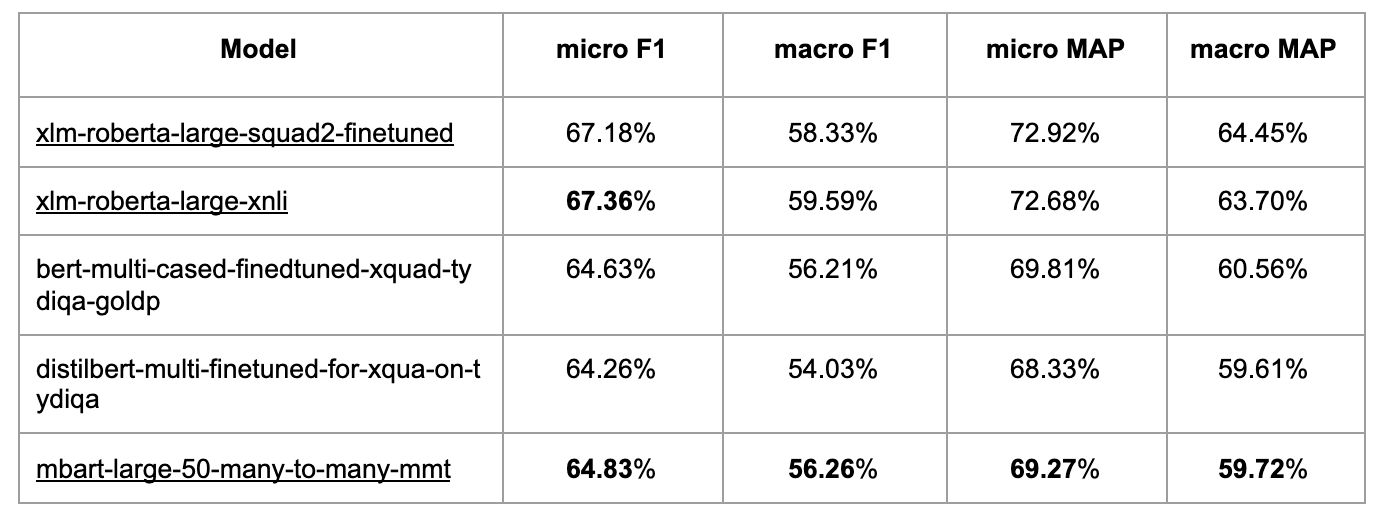

- Cross-Domain Task Finetune Pre-training: Pretraining a transformer model based on a cross-domain dataset is often helpful for many tasks. It’s also effective in boosting intent detection accuracy in our use cases. Experiments results can be found in Figures 8 and 9.

Figure 7. In-domain pre-training performance

Figure 8. cross-domain task finetune pre-training performance.

Figure 9. Multilingual task finetune pre-training performance.

Many challenging cases in our intent understanding problem require the model to have some logical reasoning capability. Similar to the finding in the logical reasoning public dataset in Yu et al. (2020), pre-training on the RACE dataset helps to boost the performance the most.

Multilingual Model

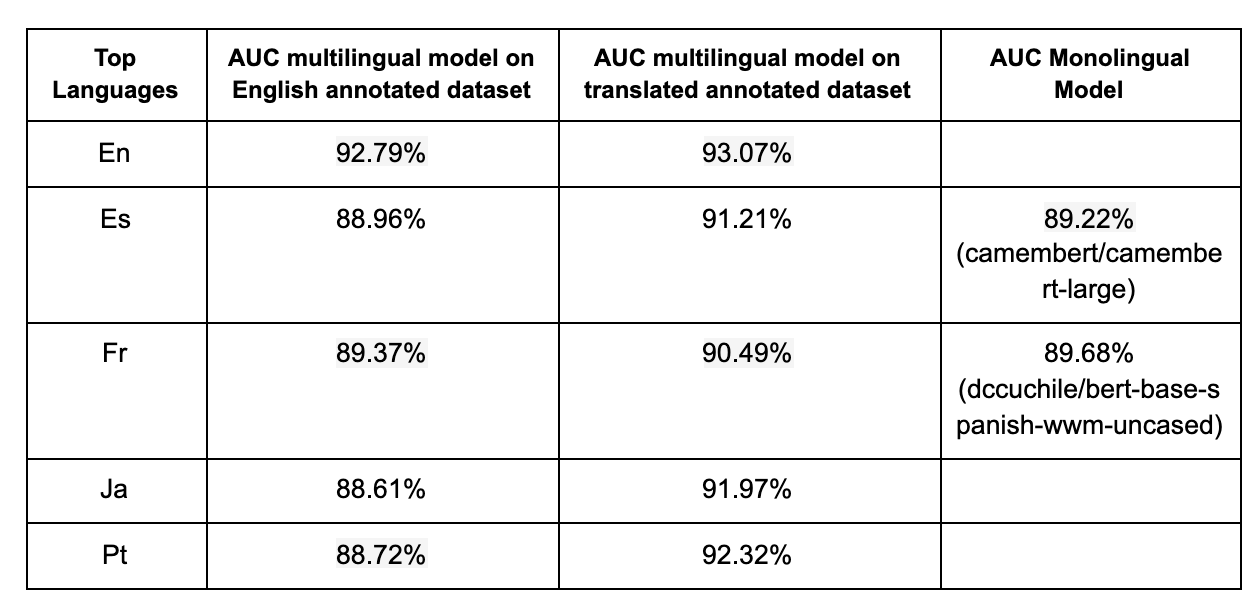

Airbnb customer support serves users from all around the world, currently supporting 14 languages. The top non-English languages, including French, Spanish, German, and Portuguese, represent around 30% of the requests. Since our model is targeted at users who speak all languages but labeled data are mainly in English, we leveraged a translated annotation dataset and multilingual model, XLM-RoBERTa, to boost model performance across all languages.

Translating the training labels to other languages is an unsupervised data augmentation technique proven effective in many deep learning training cases (Xie et al., 2020). We translate the labeled English training corpus and the labeling questions and answers into other top languages and include them in the training data to train the XLM-RoBERTa model.

We also tried training monolingual models on translated text for comparison based on public pre-trained monolingual models. Results show that multilingual models trained on translated datasets significantly outperform the English-only training dataset. Model performance is comparable with monolingual models trained by translated annotation datasets.

Figure 10. Multilingual vs. monolingual model performance.

Incorporating Multi-Turn Intent Prediction

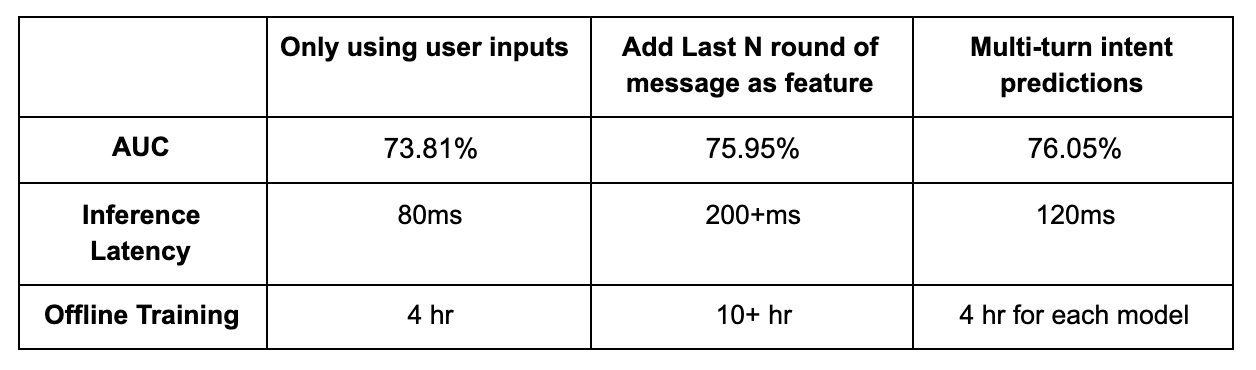

When a user comes to chatbot with a Mutual Cancellation request, we pull all the text sequences from the user’s previous conversations and concatenate the text sequences of the previous messages and the current request message together as a new text sequence input to the transformer model. This works as a dialog state tracking (Gao et al., 2019) module to incorporate the signals from user’s past interactions to better understand user intent. We experimented with two offline approaches to better consume this signal: 1) adding the last N round of messages as additional features to the current model, and 2) calculating multi-turn intent predictions on each message threshold and adding max intention score to the downstream model.

One challenge is that the computation complexity of transformer models is O(n⁴) of the sequence length, including all the previous conversions. The complexity makes it impossible to infer online in real-time. To solve this, we process the historical conversation asynchronously offline ahead of time and store pre-computer scores. During online serving, the model directly query the pre-computed scores associated to the user.

Figure 11. Multi-turn intent prediction performance and latency.

Online Serving

Deploying machine learning models online comes with a few major challenges that need to be managed differently than in the offline world.

Online Inference GPU Serving

One challenge in online serving is the latency of the model in production. We took two key steps to solve for latency requirements: 1) enabling GPU serving, and 2) leveraging transfer learning. Similar to the discussions in the section above, transfer learning techniques like teacher student model is used to reduce the amount of computation needed in online inference. In this section we mainly focus on how GPU serving helped us address this challenge.

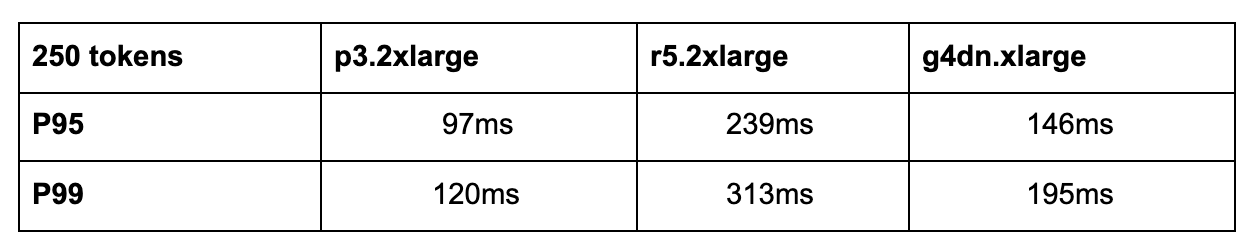

To support GPU inference, we experimented with an offline benchmark on transformer models with 282M parameters on three different instance types — g4dn.xlarge, p3.2xlarge and r5.2xlarge. Figure 12 shows the latency results across these various instance types. The general trend of latency between CPU and GPU as our input messages grow in length can be seen in Figure 13. Shifting to GPU serving has a significant impact on the online latency and is more cost-efficient.

Figure 12. GPU online serving latency for various instance types.

Figure 13. Latency using CPU vs. GPU with input message length increasing.

The results from our later online experiment (Figure 14) also show the improvement in latency from shifting to GPU inference on transformer models. With ~1.1B parameters and average input message length of 100 words, we were able to achieve ~60ms on p95, which is 3x faster on single transform and five times faster on batch transform.

Figure 14. Model latency in production before and after switching from CPU to GPU .

Switching to GPU not only improves the latency, it also allows us to run multiple model scoring in parallel. We leverage the PyTorch platform, which has built-in support for non-blocking model scoring, for better scalability.

Contextual Bandit and Reinforcement Learning

The second challenge in online serving is to adapt and optimize ML models based on new users’ online behavior. As we described in previous sections, the training data of the initial model is collected from historical user interaction over the product flow before the model is deployed. After the model is deployed, users interact with the system in a very different manner compared to the experience when the training data is collected. If the daily traffic is sufficiently large, we can always relabel the new data and update the model using the new data which reflects the updated user behavior, or directly perform multivariate testing on N policies. However, Airbnb’s CS chatbot traffic volume is relatively small compared to other ML systems such as search ranking. It will take a very long time to see the effect of any model change (either retrained model using new data or hyper parameter change).

To solve the challenge of low traffic volume, we use contextual bandit-based reinforcement learning (Bietti et al., 2019; Agarwal et al., 2017) to choose the best model and the most appropriate thresholds. Contextual Reinforcement Learning explores all the alternative problems by maximizing the rewards and minimizing the regrets. This allows us to learn from new behavior by dynamically balancing the exploration and exploitation.

We view this problem through three different actions in the product:

- a0: User is not directed through the mutual cancellation flow

- a1: User is directed to the mutual cancellation UI for guests who have already agreed with the host on the refund

- a2: User is directed to the mutual cancellation UI for cases where it was not clear if the host and guest have reached a mutual agreement

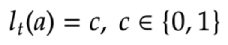

Our reward function is mutual cancellation flow entering rate and acceptance rate. The reward at time step ? for any given action can be formulated as:

where c denotes if a mutual cancellation flow is not entered/accepted.

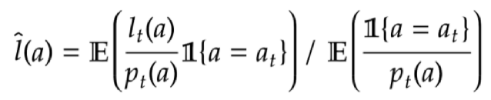

We then leveraged greedy-epsilon as our first exploration strategy. If it’s in exploration mode, we compute the probabilities for each action based on policies’ preferences and select it based on the chances. If it’s in exploitation mode, we choose the best policy. We compute the models’ thresholds based on a set of logged (x, a, r, p) tuples. We use an self-normalized inverse propensity-scoring (IPS) estimator (Swaminathan and Joachims 2015) to evaluate each policy:

In production, this approach successfully helped us explore many different models and parameter options and make the best use of the limited online traffic.

Conclusion

In this post, we introduced how we employ state-of-the-art machine learning and AI models to build support products that better serve the needs of our guests and hosts. We described how we leverage a single-choice Q&A-based model, large-scale pretraining, multilingual models, multi-turn dialog state tracking, and GPU serving and successfully tackled the technical challenges.

Interested in tackling challenges in the machine learning and AI space?

We invite you to visit our careers page or apply for these related opportunities:

Staff Data Architect, Community Support Platform

Staff Software Engineer — Machine Learning Modeling Platform

Machine Learning Engineer, Search Ranking

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cassie Cao, Hao Wang, Bo Zeng, Ben Ma, Wayne Zhang, Mariel Young , Shahaf Abileah, Pratik Shah, Brian Wang, Hwanghah Jeong, Amy Guo, Vita Papernov, Courtney Nam, Aliza Hochsztein, Mike Hinckley, Yushuang Dong, Jan Castor, Ivy Cui, Lucia Ciccio for the great contributions to Mutual Cancellation workflow development, ERF analysis and product launches. Special thanks to Alex Deng for the help on contextual bandit and reinforcement learning work; many designs are originally Alex’s idea. We would also like to thank Atul Ktal, Bahador Nooraei, Shaowei Su, Alfredo Luque for the ML infrastructure support on GPU inference. In addition, we would like to thank the contributors of open source ML libraries such as PyTorch and HuggingFace Transformers, which benefited us a lot. Finally, we want to appreciate Ari Balogh, Tina Su, Andy Yasutake, and Joy Zhang’s leadership support in leveraging machine learning on Customer Support Platforms.

References:

- Zang X, Rastogi A, Sunkara S, Gupta R, Zhang J, Chen J (2020) MultiWOZ 2.2 : A Dialogue Dataset with Additional Annotation Corrections and State Tracking Baselines. CoRR abs/2007.12720

- Jiang Y, Wu S, Gong J, Cheng Y, Meng P, Lin W, Chen Z, Li M (2020) Improving Machine Reading Comprehension with Single-choice Decision and Transfer Learning. CoRR abs/2011.03292

- Khashabi D, Min S, Khot T, Sabharwal A, Tafjord O, Clark P, Hajishirzi H (2020) UnifiedQA: Crossing Format Boundaries With a Single QA System. In: Cohn T, He Y, Liu Y (eds) Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Findings, EMNLP 2020, Online Event, 16–20 November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp 1896–1907

- Yu W, Jiang Z, Dong Y, Feng J (2020) ReClor: A Reading Comprehension Dataset Requiring Logical Reasoning. In: 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, April 26–30, 2020. OpenReview.net

- Madotto A, Liu Z, Lin Z, Fung P (2020) Language Models as Few-Shot Learner for Task-Oriented Dialogue Systems. CoRR abs/2008.06239

- Xie Q, Dai Z, Hovy EH, Luong T, Le Q (2020) Unsupervised Data Augmentation for Consistency Training. In: Larochelle H, Ranzato M, Hadsell R, Balcan M-F, Lin H-T (eds) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6–12, 2020, virtual

- Bietti, Alberto, Alekh Agarwal, and John Langford. A Contextual Bandit Bake-off. Microsoft Research. 21 Mar. 2019

- Agarwal, Alekh, Sarah Bird, Markus Cozowicz, Luong Hoang, John Langford, Stephen Lee, Jiaji Li, Dan Melamed, Gal Oshri, Oswaldo Ribas, Siddhartha Sen, and Alex Slivkins. Making Contextual Decisions with Low Technical Debt. ArXiv.org. 09 May 2017

- Swaminathan A, Joachims T (2015) The Self-Normalized Estimator for Counterfactual Learning. In: Cortes C, Lawrence ND, Lee DD, Sugiyama M, Garnett R (eds) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2015, December 7–12, 2015, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. pp 3231–3239

- Gao S, Sethi A, Agarwal S, Chung T, Hakkani-Tür D (2019) Dialog State Tracking: A Neural Reading Comprehension Approach. In: Nakamura S, Gasic M, Zuckerman I, Skantze G, Nakano M, Papangelis A, Ultes S, Yoshino K (eds) Proceedings of the 20th Annual SIGdial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue, SIGdial 2019, Stockholm, Sweden, September 11–13, 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp 264–273

All product names, logos, and brands are property of their respective owners. All company, product and service names used in this website are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, and brands does not imply endorsement