Introducing uFowarder: The Consumer Proxy for Kafka Async Queuing

Uber has one of the largest deployments of Apache Kafka® in the world, processing trillions of messages and multiple petabytes of data per day. Three years ago, we built a push-based consumer proxy for Kafka’s Async Queue. It’s become the primary option for reading data from Kafka in pub-sub use cases at Uber, with over 1,000 consumer services onboarded. We open-sourced the solution under the name uForwarder.

This blog describes the challenges we faced when productionizing uForwarder and the solutions we implemented to optimize hardware efficiency, ensure consumer isolation, address head-of-line blocking, and support message delay processing. By reading this blog, you can understand the thinking behind uForwarder before applying it to your use cases.

We broke down the motivation and high-level solutions for uForwarder in a previous blog. In short, we encountered problems like partition scalability, head-of-line blocking, and support issues for multiple programming languages.

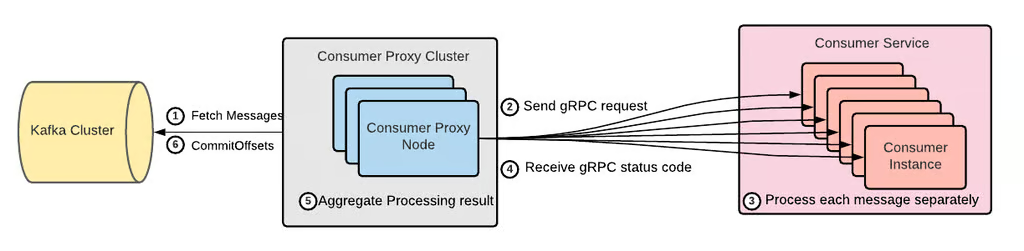

We developed Consumer Proxy, a novel push proxy, to solve those challenges. At a high level, the Consumer Proxy cluster:

- Fetches messages from Kafka using Kafka’s binary protocol.

- Pushes each message separately to a consumer service instance that exposes a gRPC® service endpoint. The consumer service processes each message separately, and sends the result back to the Consumer Proxy cluster.

- Receives the gRPC status code from the consumer service.

- Aggregates the consumer service’s message processing results.

- Commits proper offsets to Kafka when it’s safe to do so.

Figure 1: High-level Consumer Proxy architecture.

The Consumer Proxy abstracts away the complexity of managing Kafka consumers, offering service owners a familiar gRPC interface instead of direct interaction with Kafka. It addresses the impedance mismatch of Kafka partitions for message queuing use cases and prevents consumer misconfigurations and improper consumer group management by hiding these details from consumer service.

We encountered several new challenges after productionizing uForwarder and as we onboarded more use cases.

In a previous blog, we introduced the head-of-line blocking problem. We found that out-of-order commits can improve resiliency to transient poison-pill messages. So, we introduced a dead-letter queue to mitigate permanent poison-pill messages.

But, the queue relied on the fact that a consumer service could receive any message, and could send responses back to the Consumer Proxy. The problem was, there were exceptions. A message might fail in transit and not be able to reach the consumer handler. This could happen for reasons like:

- Message size limit. By default, the gRPC server limited the max payload request size to 4MB. For any message over the size limit, the consumer handler wouldn’t even receive the message.

- Invalid consumer instances. With traffic isolation, certain messages are routed to specific consumer instances. However, if any of these targeted instances are not functional, the corresponding messages wouldn’t be able to reach the consumer handler and become poison-pill messages.

- Request filtering. There are various reasons a consumer service was built with interceptors. Interceptors could fail requests before reaching the consumer handler.

When any poison-pill message appeared without being detected or mitigated in time, the consumer got blocked.

The size of the Consumer Proxy fleet needed to scale with the size of its workload. We started running a cluster with two digits of servers in the early days, but as more consumers migrated to the Consumer Proxy, the fleet grew into multiple clusters with hundreds, eventually thousands of servers. Facing rapidly growing hardware costs, improving hardware utilization to make the solution more efficient became a critical problem.

As more services adopted the Consumer Proxy, multiple consumer services faced the challenge of an external upstream data source not being ready when events arrive. This timing mismatch caused teams to implement repeated checks, fallback retries, or integrate with separate delay mechanisms. It complicated their overall architecture and added more dependencies. Often, consumer services had to wait longer than necessary, negatively impacting performance and reliability.

A built-in delay processing feature in Consumer Proxy can address these issues by eliminating the need for retries and simplifying their workflows. It also reduces operational overhead by centralizing delay logic in one place instead of scattering it across multiple services.

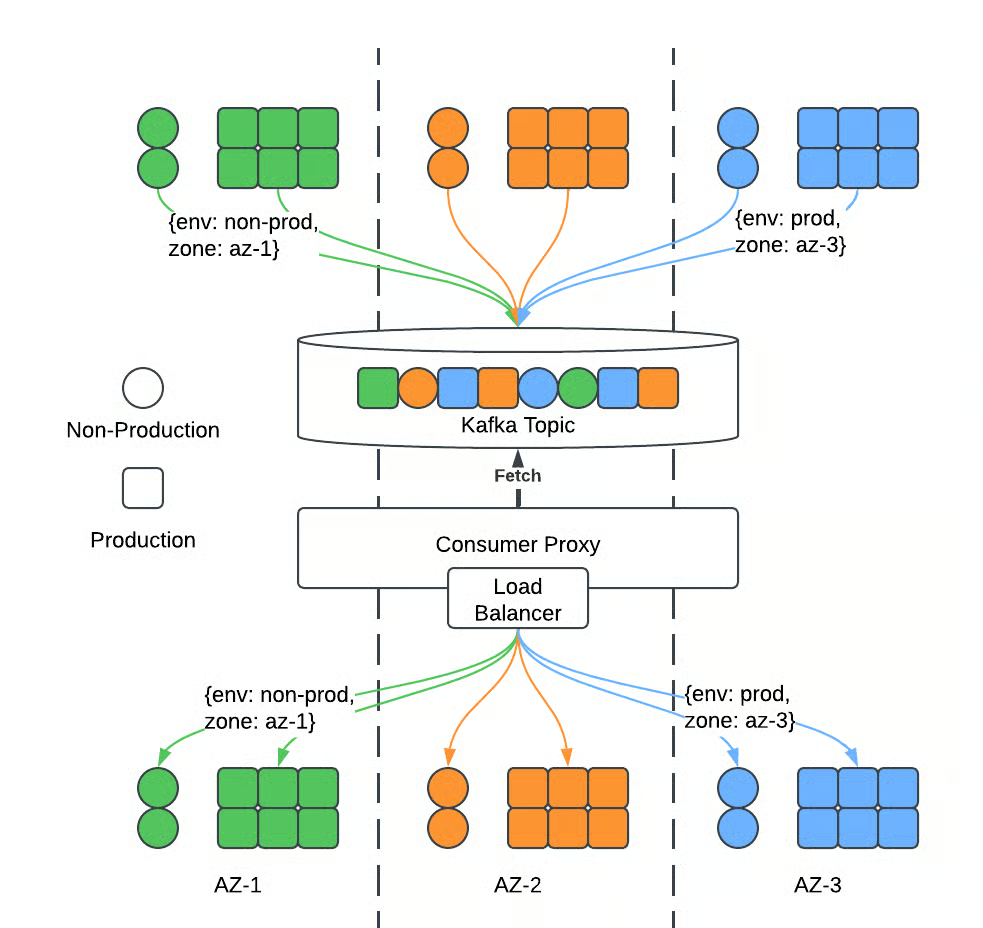

With Consumer Proxy, the typical way a message routes to a consumer service is through a network load balancer that is supposed to distribute workload to all consumer service instances. In this case, all consumer service instances share all messages. As infrastructure evolved, there were more and more demands to have message isolation.

Production/non-production isolation isolates production messages in a production service and non-production messages in a non-production service to service reliability or meet compliance requirements. Consider this example. Suppose there’s a producer service that exposes an API. The API converts the request payload into a message and produces a Kafka message. Sometimes the caller service is a non-production service, so the message produced contains non-production data. For the topic consumer, it may receive both production and non-production messages. Non-production messages could fail a production service or pollute production data.

Uber services run in multiple regions, and each region has multiple availability zones. As both the producer service and consumer services run in multiple zones, a producer service failure in one zone could fail consumer services in any zone. To minimize the blast radius of zone failure, zone isolation intends to isolate messages in the same zone across producer and consumer services.

This section explores solutions we have made to address production challenges with uForwarder.

Context-Aware Routing

A naive way to deliver certain messages to specific consumer instances is to divide a Kafka topic into multiple child topics, and make each consumer instance consume one child topic. But that way quickly became unfavorable because of backward compatibility. One topic used by messaging could also be used in streaming analytics, data ingestion, and more. Our solution required many changes to all of them.

To solve this problem, we chose context-aware routing. With this solution, the producer service injects subsetting context into a Kafka message as a message header. Consumer Proxy converts context from the message header to the gRPC request header. The load balancer performs context-aware routing according to the request header.

Figure 2 shows a message routed from a producer service to a consumer service with both zone isolation and production or non-production isolation.

Figure 2: Context-aware routing.

For Consumer Proxy, there’s no more severe problem than a completely stuck consumer. A poison-pill message is the top risk that could get a consumer stuck. In a previous blog, we introduced a dead-letter-queue as the solution. However, it can’t solve the fail-in-transit problem. Anticipating that risk, we introduced an active head-of-line blocking resolution solution.

The solution has two components: head-of-line blocking detection and mitigation.

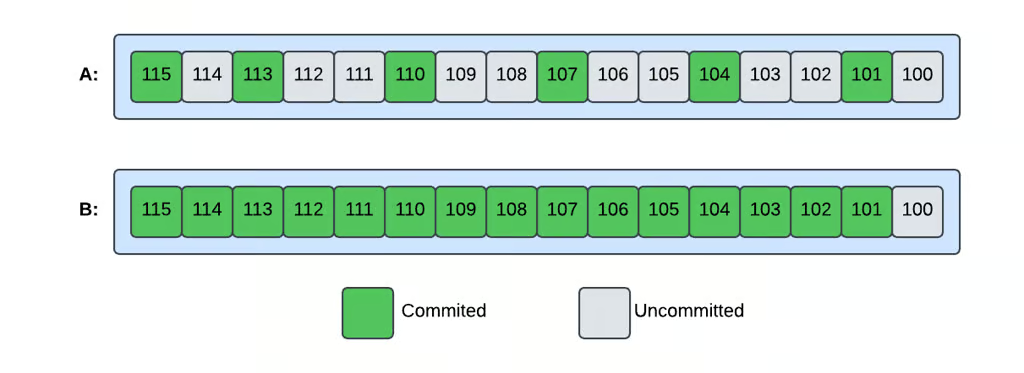

In the previous blog, an out-of-order commit was introduced to support parallel processing. The out-of-order commit tracker is the data structure that tracks the commit status of each offset per topic partition. By observing its status, we can identify head-of-line blocking.

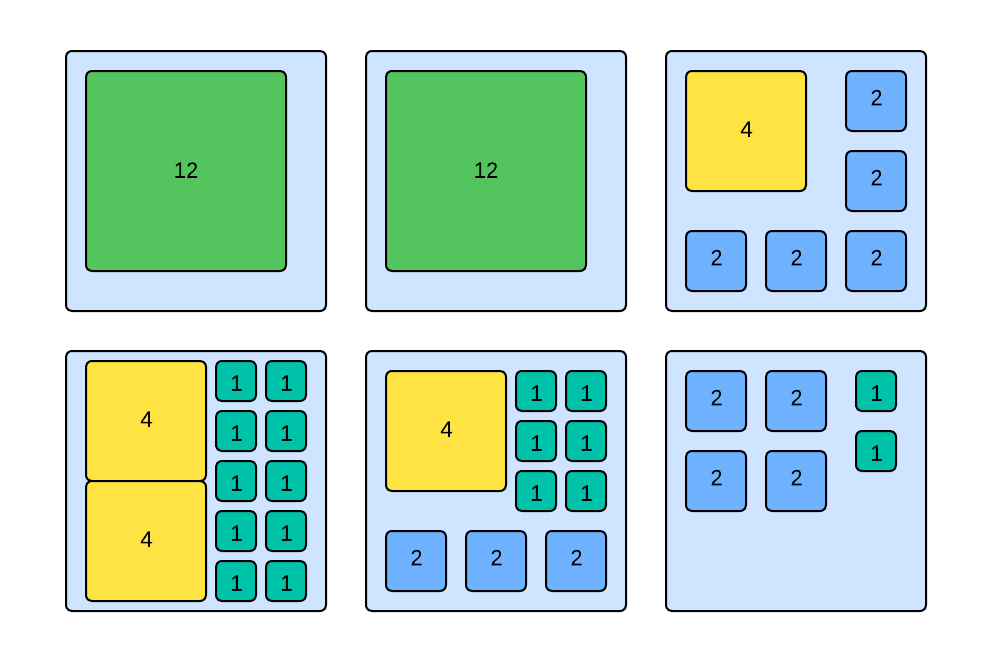

There are two facts to consider when evaluating the risk of head-of-line blocking: utilization of the tracker and the percentage of uncommitted messages. The first fact is easy to understand. A queue won’t be blocked as if the tracker still has an empty slot. For the second fact, consider the trackers in Figure 3. Which one has a higher probability of head-of-line blocking?

Figure 3: States of the out-of-order commit tracker.

Tracker B has a higher probability of head-of-line blocking because head-of-line blocking is a small amount of messages blocking the majority of messages, so the fewer uncommitted messages there are, the more likely it’s a head-of-line blocking situation.

The detected condition is:

- Utilization of tracker > UTILIZATION_THRESHOLD

- Percentage of uncommitted messages < UNCOMMITTED_PERCENTAGE_THRESHOLD

In practice, we use 90% as the UTILIZATION_THRESHOLD and 2% as the UNCOMMITTED_PERCENTAGE_THRESHOLD.

Once head-of-line blocking was detected, mitigation was the next step. The goal of mitigation is to get the offset at the head of the queue committed without causing data loss. The mitigation procedure involves these actions:

- Mark the offset status in the tracker as CANCELED.

- Cancel gRPC requests, including ongoing or future retries.

- Send the message to the dead-letter-queue.

- Mark the offset status in the tracker as COMMITTED.

Consumer Proxy offloads the rebalance process from a consumer service, so the consumer service is turned stateless. This change makes consumer services run much more efficiently because workloads now can be evenly distributed to all consumer instances. However, the rebalance procedure still exists. It just relocated from the consumer service to Consumer Proxy. Workload placement needs to be optimized for cost efficiency.

To make Consumer Proxy run more efficiently, we considered two problems: workload sizing and workload placement.

Multiple dimensions of resource need to be considered when calculating the size of a workload, including CPU, memory, network, and more. Resource demands for different workloads are different. For example, a workload with a higher request rate needs more CPU. Similarly, a workload with higher concurrency needs more memory, and a higher bytes rate needs more network capacity.

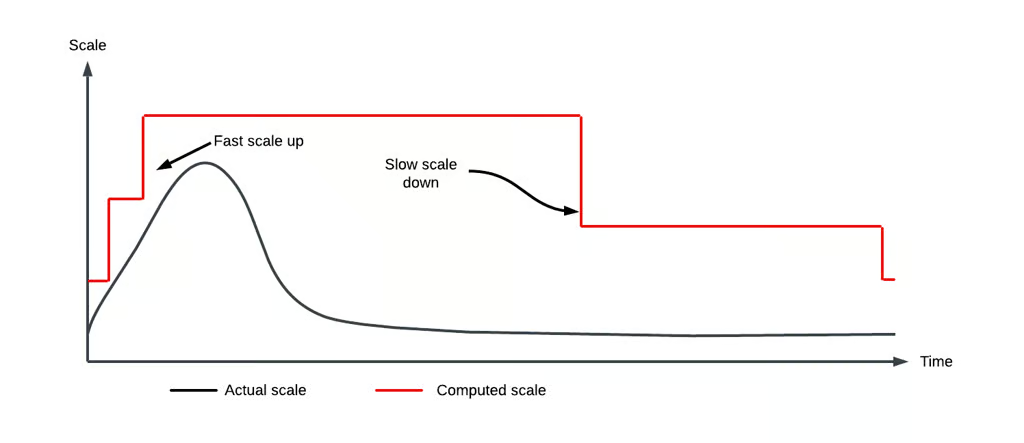

Consumer Proxy uses an adaptive way to determine the size of the workload: by observing traffic metrics, it determines the size of hardware resources for each workload. Consumer Proxy continuously runs the procedure to ensure eventual convergence of computed scale and actual scale of the workload. When adjusting the scale of the workload, we use different time windows for up and down scale to achieve fast scale-up and slow scale-down. This minimized impact of consumer lag caused by insufficient hardware resource and minimized message duplication caused by workload placement shuffle.

Figure 4: Fast scale up, slow scale down of workloads.

Workload placement solved the problem of placing workloads of various sizes on worker instances of fixed sizes. The Consumer Proxy controller runs a rebalance procedure that continuously moves workload between worker instances. Once a workload is assigned to a worker, the assignment becomes sticky. It won’t change unless a placement violation is detected. It could be a workload size violation or a worker’s liveness check failure.

Workloads of different sizes can pack into the same worker instance given the total size of the workload is within the worker’s capacity.

Figure 5: Workload placement on worker instances.

With this solution, Consumer Proxy can make sure hardware resources get used efficiently while keeping worker instances from being overloaded.

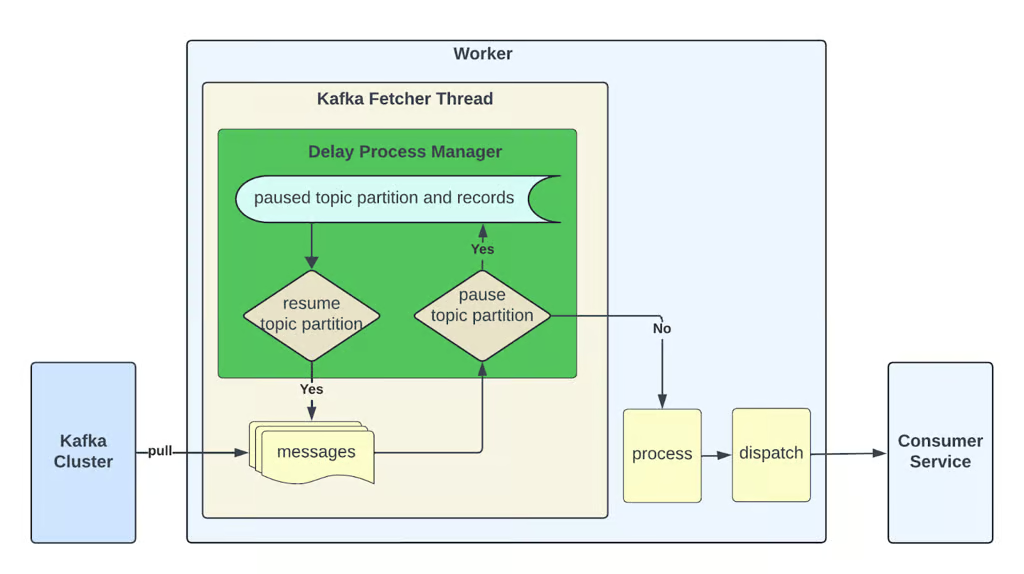

Previously, Consumer Proxy supported delay processing in retry topics. For each message in a retry topic, the associated fetcher thread checks whether the predefined delay has elapsed. If the delay is satisfied, the message is submitted for processing and then dispatched to the consumer service. Otherwise, the fetcher thread pauses until the required delay is passed.

However, this method has a key limitation. The fetcher thread remains completely paused and can’t process any messages until the current message’s delay has been met. To avoid blocking additional message consumption and wasting compute resources, we restricted the retry topic to a single partition.

Figure 6: Delay processing in Consumer Proxy worker fetcher thread.

Kafka topics natively support multiple partitions for scalability, so we can’t apply the above delay processing method to Kafka main topics. To maintain scalability while enabling delay processing in main topics, we introduced DelayProcessManager into the Consumer Proxy fetcher thread. It performs these functionalities:

- Verify delay. For the first unprocessed message in a topic partition, DelayProcessManager checks whether the required delay period has been satisfied.

- Pause partitions. If the message hasn’t yet met the delay time, DelayProcessManager pauses the corresponding topic partition. It then stores the polled but unprocessed messages in an in-memory buffer to prevent repeated polling of the same messages and avoids unnecessary resource consumption.

- Resume partitions. Before the fetcher thread polls new messages from Kafka clusters, the DelayProcessManager resumes any topic partitions that have now met the delay requirement. It merges the previously stored unprocessed messages with the newly polled messages for processing.

This design pauses only topic partitions that require a delay, rather than pause the entire fetcher thread. The other topic partitions within the same thread can continue message delivery without interruption. Additionally, this approach is applicable to retry topics, which enables them to support multiple partitions seamlessly.

It’s important to note that the design guarantees an at-least delay, not an exact delay. The DelayProcessManager resumes topic partitions only after workers have completed processing the current batch of messages. Consequently, if the processing time for the current batch exceeds the predefined delay, the actual delay could be longer than the predefined delay time.

After the publication of our previous blog, multiple companies reached out to exchange ideas and discuss similar pain points. As it seemed beneficial to the industry, we open-sourced the uForwarder project and began building a community to improve it together.

We’re actively working on more features to further enhance the messaging queue capacity of uForwarder.

Consumer lag is one of the most common issues with Kafka message queues, and it can have a significant impact on real-time services like Uber. To mitigate the delays caused by consumer lag, we plan to rewind the Kafka consumer offset to the latest while spinning up a side consumer to catch up on lagging data. This approach helps us achieve a good balance between data freshness and data completeness.

gRPC/Protobuf is the primary protocol for service-to-service communication at Uber. Supporting the Protobuf data format in our stack is a common request from stakeholders, especially for uForwarder, as we already leverage gRPC to dispatch Kafka messages to consumer services. It’s natural for our stakeholders to expect to receive Protobuf objects directly, rather than the raw Kafka bytes that they’d need to decode themselves. We’re actively working on building this support.

In our work on Consumer Proxy, we addressed critical challenges like head-of-line blocking and hardware efficiency and covered essential features like context-aware routing for better message isolation and a delay processing mechanism. We’ve open-sourced Consumer Proxy as uForwarder, and welcome contributions, feedback, and collaboration to make uForwarder better.

Apache®, Apache Kafka®, Kafka® and gRPC® are registered trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation in the United States and/or other countries. No endorsement by The Apache Software Foundation is implied by the use of these marks.