Migrating Airbnb’s JVM Monorepo to Bazel

[

Press enter or click to view image in full size

At Airbnb, we recently completed migrating our largest repo, the JVM monorepo, to Bazel. This repo contains tens of millions of lines of Java, Kotlin, and Scala code that power the vast array of backend services and data pipelines behind airbnb.com.

Migration in numbers (4.5 years of work):

- Build CSAT: 38% → 68%

- 3–5x faster local build and test times

- 2–3x faster IntelliJ syncs

- 2–3x faster deploys to the development environment

In this blog post, we’ll discuss the why, share some highlights on the how, and finish off with key learnings.

Why Bazel?

Before the migration, our JVM monorepo used Gradle as its build system. We decided to migrate to Bazel because it offered three key advantages: speed, reliability, and a uniform build infrastructure layer.

Speed

Bazel’s cacheable, portable actions allow us to scale performance with remote execution

In 2021, builds of large services often took >20 minutes locally and pre-merge CI p90 was 35 minutes.

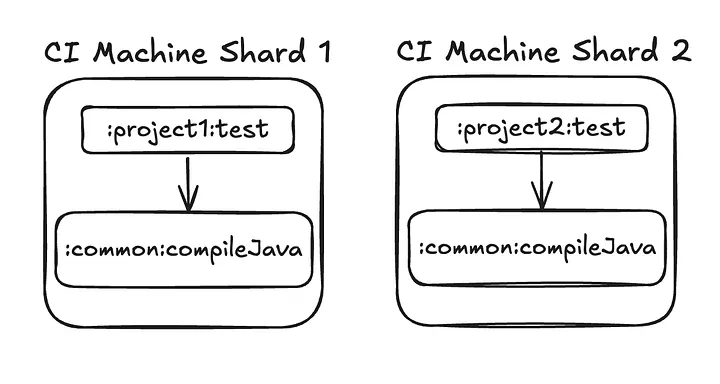

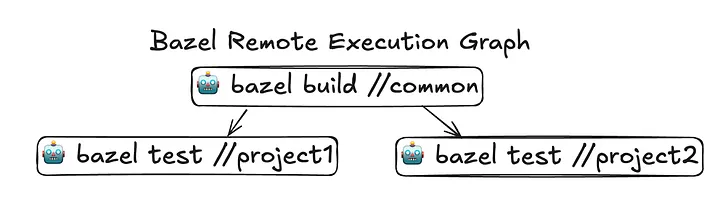

Building with Gradle was near its limit. We had already vertically scaled to high-end AWS machines on CI and remote development machines for developers of large services. In CI, we also used heuristics to split project builds and tests across multiple machines. However, this was inefficient, because of machine underutilization and duplication of shared tasks.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Bazel remote execution allowed us to scale to thousands of parallel actions. This was far more efficient than our sharding heuristics. Remote build execution (RBE) workers are also short-lived, which results in better machine utilization and cost efficiency. In addition, Build without the Bytes allows downloading only a subset of files, greatly reducing download volume (in Gradle, every cached artifact needs to be downloaded). Finally and most importantly, local builds are significantly faster thanks to RBE.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

In addition, Gradle configuration of some large projects often took minutes due to it being single-threaded. Bazel analysis, in contrast, runs in parallel, in part because its configuration language, Starlark, is constrained to be side-effect-free.

Reliability

Bazel’s hermeticity ensures reliable, repeatable builds

Gradle tasks have access to the full file system, which can lead to serious unintended consequences at scale. One example we ran into was when a developer updated a task to clean up recent files in the /tmp/ directory. This created a race condition with other Gradle tasks that used the /tmp/ directory and caused CI to fail when thousands of Gradle tasks had to be rerun.

Bazel solves this issue with sandboxing, which ensures that only specified inputs are available to a build action. If a file isn’t declared as an input, it simply doesn’t exist in the sandboxed environment.

Gradle tasks also implicitly depend on the machine’s resources. Gradle builds run on local machines and CI machines of different sizes. This can lead to resource contention when a task is run on a smaller machine or when the cache is cold and thousands of tasks are run on the same machine.

Remote build execution (RBE) solves this by running actions in identical containers with strict resource limits. We also configured both local and CI builds to use RBE, which greatly reduces environment differences.

Shared infrastructure

Airbnb currently has a collection of language- and platform-specific repos, such as web, iOS, Python, and Go, all of which are now on Bazel. Unifying on Bazel enables a uniform build infrastructure layer across repos, which includes:

- Remote caching

- Remote build execution

- Affected targets calculation

- Instrumentation & logging from the Build Event Protocol

How did we migrate?

As a first milestone, we wanted to show that we could build a service and run its unit tests in Bazel. Because this was a proof of concept, we wanted to minimize disruption to engineers. Therefore, the Bazel build co-existed with Gradle**.** As a result, developers could choose between using Gradle or Bazel locally_._

We needed to prove that developers would choose to opt in to using Bazel over Gradle. It wasn’t enough for Bazel to be faster, developers had to willingly opt in to using Bazel.

For this proof of concept, we chose Airbnb’s GraphQL monolith platform, Viaduct, which had the following important properties:

- It was one of Airbnb’s largest and most complex services. If we could migrate Viaduct to Bazel, then we could likely migrate the rest of the monorepo.

- Slow builds were a major pain point, so Bazel could have a large impact.

- Viaduct has 300 product engineers modifying its code every month, so improving Viaduct’s build speed would be a substantial productivity win.

- Because of (2) and (3) above, Viaduct’s core infrastructure team was eager to partner with us.

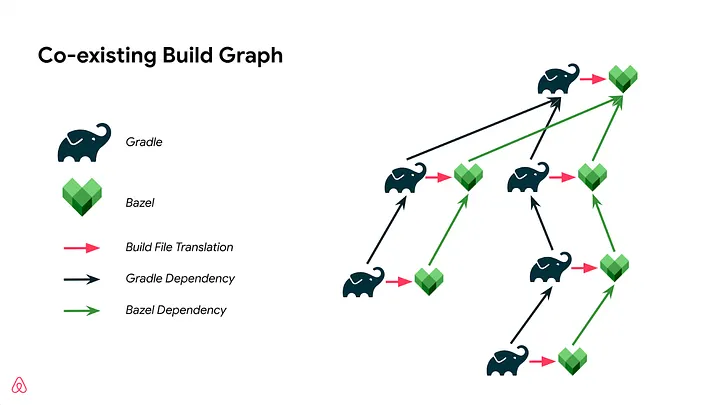

To achieve a working Viaduct build with Bazel, we did two things. First, we had to port much of Viaduct’s build logic from Gradle to Bazel. Second, because we decided to maintain co-existing builds and the Gradle build graph was still changing, we decided to build an automated build file generator (which we’ll cover in detail in a separate section).

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Importantly, even though we were able to locally build the service 2–4x faster with Bazel, many developers did not yet want to switch.

In talking with the service’s owners, we discovered a number of missing integrations and bugs. It took us an additional few months to address these pain points, after which Viaduct developers willingly switched from Gradle to Bazel.

Scaling builds and tests with Bazel

The proof of concept showed that Bazel was superior to Gradle for one of Airbnb’s largest services and a large audience of developers. Now we wanted to scale it to the rest of Airbnb’s JVM monorepo.

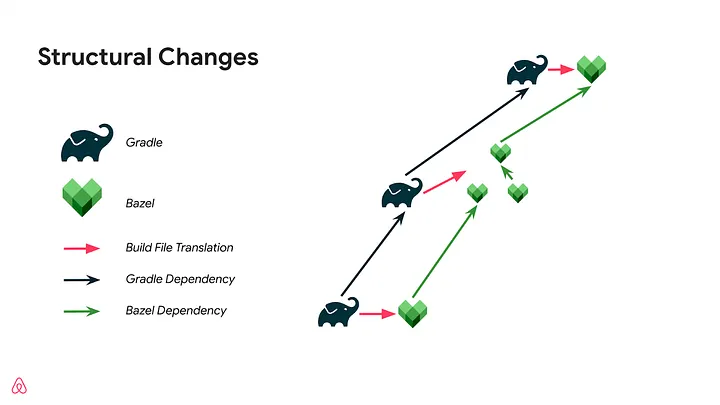

We decided to scale breadth-first, getting all of the repo compiling and testing in Bazel. Again, to minimize disruption, Bazel builds co-existed with Gradle, which had two important benefits.

First, developers could still use Bazel for local development and get most of its benefits even though their code was still built with Gradle for deployment. Second, we could always disable Bazel if it was negatively impacting developers. For example, when Bazel infrastructure like the remote cache or remote execution cluster experienced an incident, we could and did disable Bazel, letting users fall back to Gradle.

However, a major downside was that both Gradle and Bazel build graphs had to be maintained. Manually maintaining a Bazel build graph would have degraded the developer experience. As a result, we invested further in automated build file generation, so that developers didn’t need to manually maintain Bazel build files.

Automated build file generation

For our build file generator, we were heavily inspired by Gazelle, which generates Bazel build files by parsing source files to build a dependency graph.

Although we considered extending Gazelle to support JVM languages, we had very strict performance requirements and needed to handle dependency cycles. This ultimately led us to build our own automated build file generator.

Because we had to maintain co-existing build graphs, we needed to run the build file generator on every commit before merging into mainline. This meant it had to run as fast as possible to not significantly degrade the developer experience. To achieve this, we implemented external caching to speed up the automated build file generation.

Similar to Gazelle, the build file generator parses Java, Kotlin, and Scala source files for package and import statements and symbol declarations to build a file-level dependency graph.

In CI, we publish a cached index of the repository at each mainline commit. When a user runs sync-configs, it downloads this cache and only re-scans directories which have changed since the merge base. This greatly improves performance for the common case where users only modify a small set of files.

In addition, with this build file generator, we were able to support a more fine-grained build graph, which resulted in >10x more Bazel targets than Gradle projects. This enabled faster builds through more parallel builds and less cache invalidation. However, one challenge of moving to a more fine-grained build graph is the possibility of introducing compilation cycles; sync-configs is able to detect this automatically and merge compilation units when necessary.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Even after the migration, the build file generator remains in use. It improves the developer experience by automatically fixing build file configurations and removing unused dependencies. In contrast, when we were on Gradle, users manually maintained ~4,500 Gradle files, which led to unused dependencies, a bloated dependency graph, and slower builds with fewer cache hits.

Porting build logic

In addition to JVM source files, our repo has a large amount of build logic such as code generation owned by multiple teams. These often took the form of Gradle plugins.

Because we now had automated build file generation, when porting the build logic, we also had to integrate it with the build file generator. Also, because we had more granular targets, a single line of Gradle config now might need to apply to 10+ Bazel build files.

As a result, our build file generator architecture supported plugins similar to Gazelle extensions. These plugins were triggered by the presence of specific files such as Thrift or GraphQL files. These plugins could also generate new build targets such as codegen actions.

In some cases, the Gradle logic was manually added as a one-off or not easily inferred from the file structure. As a result, we also supported generator directives similar to Gazelle, such as adding dependencies or setting attributes.

Initially, our team ported much of this build logic ourselves with minimal help from service owners. As Bazel adoption grew, owners of complex build logic were incentivized to migrate to Bazel, because it was faster and more reliable than Gradle. In the process, they often wrote their own build file generator plugins, highlighting the extensibility of our generator.

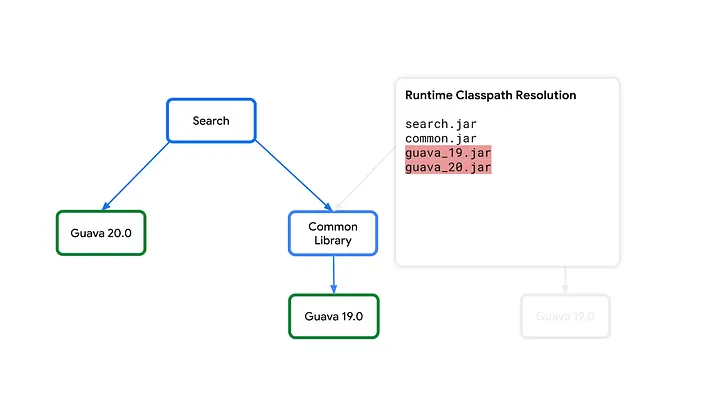

Third-party library multi-version support

Another major issue we hit on the road to 100% compilation and testing with Bazel was multiple versions of the same third-party library.

Initially, we specified a single version of each library. The build file generator would add dependencies from this universe.

However, in Gradle, each sub-project within the monorepo could use different versions of third-party libraries. As a result, when compiling against a single version, compilation or testing could fail with a missing symbol.

To bring multi-version support to our Bazel system, we built tooling to generate multiple maven_install rules and added a custom aspect to resolve conflicts at the target level.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Multiple versions of Guava in Bazel before we added conflict resolution

Once we had this capability, we systematically synced library versions from Gradle so that each build target’s classpath more closely matched its Gradle counterpart.

To learn more about our approach, see our BazelCon 2022 talk. Since giving this talk, we have made improvements like moving the resolution to analysis-time for better IDE support and adding more user-friendly tooling for updating libraries.

Migrating the deploys

As we got the vast majority of projects building and passing unit tests with Bazel in CI, we began to focus on migrating deployments. The Bazel-built `.jar`s were not identical to the Gradle-built `.jar`s. As a result, we needed a strategy to ensure the deployments were safe. We started with services.

Services

To verify the correctness of deploying services with Bazel, we used startup and integration tests. Of ~700 services, ~100 encountered startup or integration test failures. The majority of failures were missing dependencies that were loaded via Java reflection, usually from config files or other files. As a result, we were able to fix a number of these issues by parsing files for classes that would be loaded via reflection, and then adding the required dependency.

Another major source of errors was differing library versions, which could lead to missing symbol errors at runtime. In Gradle, users manually specified dependencies and their versions. However, in Bazel, build files were generated from source and dependencies were inferred from import statements, which didn’t specify the version. We solved many of these errors forcing third-party library versions to match those of the Gradle project.

After taking into account reflected classes and syncing versions, only a single-digit percentage of services hit production runtime issues that required more in-depth manual work to fix.

Data pipelines and other projects

In addition to services, we had 450 data pipelines and ~50 other projects that were deployed to either a Spark cluster or a Flink runtime.

Similar to services, we were able to catch a number of issues using tests. In particular, data pipelines on Airbnb’s data engineering paved path have CI tests that run a small version of the Spark pipeline locally. For these ~400 paved-path pipelines, after passing CI tests, only about 3% had production issues at runtime. As a result, we were able to very quickly migrate the paved-path pipelines.

As with services, we had a few remaining deployables that were a bit more bespoke and had to be individually deployed and monitored to verify correctness.

What did we learn?

Early in the migration, we identified key pilot services that had large opportunities for impact and an appetite to invest in migrating to a new build system. For example, Viaduct had complex build logic leading to slow builds and reliability issues. In addition, many developers contributed to the service, so improving their builds had a large impact on Airbnb’s developer experience.

Partnering with pilot teams was incredibly valuable. They were early adopters and made significant contributions in the form of reporting and debugging issues, profiling performance bottlenecks, and suggesting features. The pilot teams also became advocates and provided internal support, helping motivate the rest of the Airbnb developer community.

Dangers of premature optimization

This migration took 4.5 years. With the benefit of hindsight we think we could have drastically improved the migration timeline if we had migrated first, before improving*.*

Although increasing build granularity improved build times, it increased the time to migrate. Specifically, increased build granularity greatly increased the number of configuration files, making it much harder to manage configurations manually. This forced more functionality into automated build file generation, which increased its complexity.

If we had migrated first and then optimized the build granularity, we believe we could have migrated sooner, enabling users to get benefits from Bazel sooner and reducing the time spent maintaining two co-existing builds.

Similarly, build granularity also made it harder to match deploy `.jar`s between Gradle and Bazel. This led to spending more time testing deployments and fixing runtime issues.

On a more positive note, we accelerated the migration by deciding to support multiple third-party library versions and implementing version resolution. This enabled us to sync versions from Gradle to Bazel, which fixed a large number of build and runtime issues.

Towards the end, one major takeaway in the migration was, by default, we should try to imitate what was there before*.* In our case, deviating from Gradle usually added technical risk, and should be carefully considered, especially its downstream consequences.

As engineers, we often want to improve things. However, during migrations, improvements can have non-obvious consequences and potentially significantly slow down the migration.

🏁 Conclusion

After 4.5 years, we fully migrated Airbnb’s biggest repo from Gradle to Bazel, achieving:

- Build CSAT: 38% → 68%

- 3–5x faster local build and test times

- 2–3x faster IntelliJ syncs

- 2–3x faster deploys to the development environment

Finally, now that several Airbnb repos are on Bazel, we’re able to share common infrastructure such as remote build caching, remote build execution, affected targets calculation, and more.

Interested in helping us solve problems like these at Airbnb? Learn more about our open engineering roles here.